Through the Other Looking-Glass, and What I Found There

On becoming whole again after losses that shatter

Writer’s Note: This essay features a touch of Shape Poetry, where some words appear in the shape and form of what they describe. If you’d like to see the intended shape, it’s best viewed from your desktop browser on the Substack website (instead of email or the app)

This is a story that begins in a million pieces.

A Million Pieces

By the time I was 26, I found myself having lived on four continents, in five countries and across six cities.

And I didn’t know what I did mean.

Each time I returned to visit family and friends who I had grown up with in Singapore, I felt a stranger and stranger sensation.

Like I was getting smaller and smaller, somehow, each time.

“What does it feel like, to have lived in so many places?” someone once asked me.

It felt like there were a million pieces of me, swimming by themselves all around the world.

It felt like there were always pieces and pieces of me somewhere else, that the person in front of me could never see.

And I didn’t know how to begin to collect them back together to be one whole me.

Natural Magic

The kaleidoscope was born from many different people, over centuries, spending their days looking through glass, at many different pieces of things.

At the very beginning, there had been a seed of discovery —

multiple reflections are created

when light bounces back and forth

between two or more

reflecting surfaces

multiple reflections are created

This was first recorded between 1558 to 1589, in the book Magia Naturalis (Natural Magic)1, by Giambattista della Porta. A Renaissance Italian polymath and playwright, he was also known as the Professor of Secrets (specifically, those secrets held within nature and the forces of nature).

For the next two and a half centuries, others continued studying this phenomenon, without much revelation.

Until one day in 1815, a Scottish physicist, Sir David Brewster, who had been conducting experiments on light, noticed an interesting effect.2

He noticed that an apparently mundane bit of cement, when subject to multiple, repeated reflections using reflecting glasses set at different angles to each other, was capable of producing reflected images of unexpected beauty and symmetry.

Transparent, Like Glass, Transparent

Transparent, like glass —

is the umbrella through which Charlotte looks up and around her at the rain-blurred city scape of Tokyo in the film, Lost in Translation.

She’s been wandering around Tokyo, searching for nothing, waiting for it to turn into something.

She looks at the city through many mediums — her transparent umbrella, her analog camera, her hotel room window from the highest floors of the Park Hyatt, the gates of a Zen temple garden.

Until one day, not so long after, she finds herself looking at the city through a medium different from all the others — she looks through the eyes of Bob, a fellow American who finds himself adrift in Tokyo at the same time.

And they discover that they can see into each other.

That all that’s between them is —

like glass, transparent.

The Spaces Between

“I sometimes treat space as a main character in my films… we’re looking at things from afar. It gives you space to think and feel, rather than just identifying with the main characters.”

— Wong Kar Wai, In The Mood for Love

In The Mood For Love is a film about a man and a woman connected in time, and separated in space — from themselves, from each other, and from us.

Transplanted from Shanghai to British-ruled Hong Kong in the 1960s, Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung play the woman and man who come together because of the secrets of others (they suspect their married partners are having an affair with each other).

An exploratory space for the imagination opens up on screen, reflecting back to us the unspoken secrets of inner worlds — the main characters’ and our own.

We start to notice the spaces that exist — between the lines, between things, between people, between our sense of who we are and the constrained forms of lived expressions we permit of ourselves.

We start to notice that Maggie’s cheongsams, when they appear in the movie’s frames, are enclosed by space.

Each cheongsam flows as a contoured silhouette that simultaneously contains and constrains.3

The infinite-seeming colours and textures of her cheongsams speak all at once of her inner world rich in yearnings and desires, and her outer world impoverished by their non-expression.

We start to notice the city of Hong Kong herself — unfolding as the helplessly silent walls, corridors, streets and buildings that bear witness to the two characters’ inner and outer worlds — becoming a character in the film too.

A character today unable to return to who she was in the 1960s, speaking to us of the essence of that era, reflecting back to us the essence of ungraspable nostalgia we feel for our own lost longings and yearnings.

A character holding for us the secrets that have no place to go.

The Pursuit of Beauty

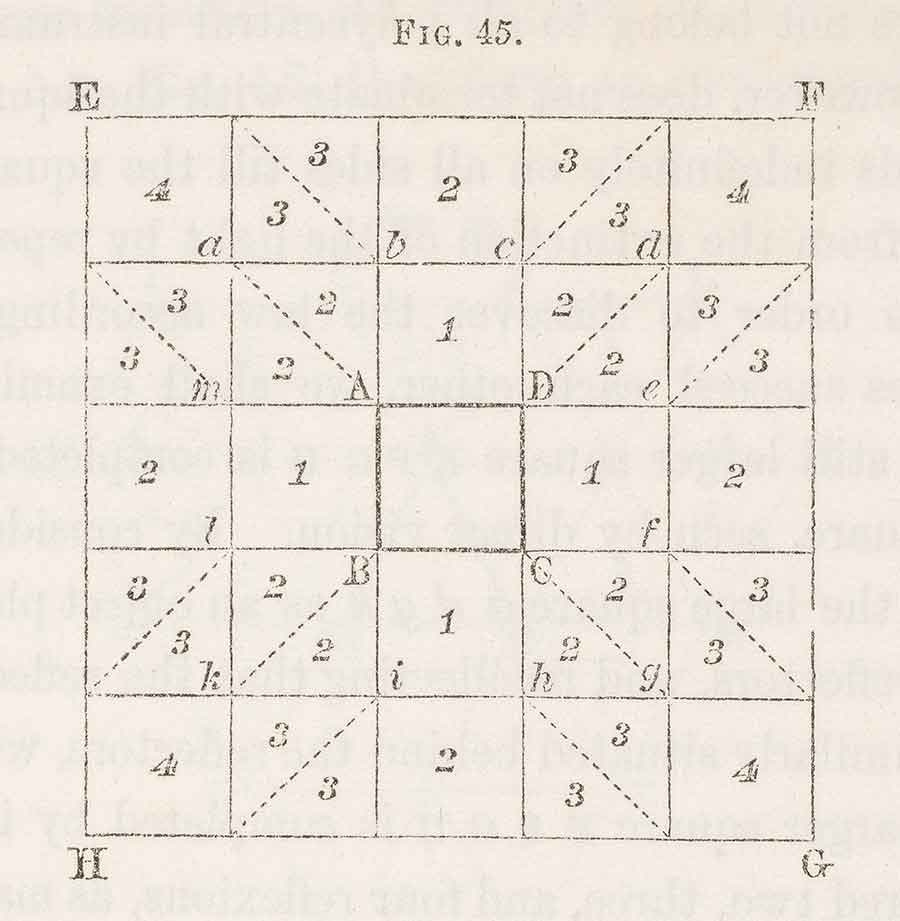

Fascinated by the untold secrets held by multiple reflections of light, Brewster set out to experiment further to identify the conditions for creating the most beautiful and symmetrically perfect images.

He collected disparate, coloured glass pieces and other irregularly shaped objects and fixed them in place as a base for multiple reflection, via a column of mirrors spaced apart at angles to each other.

Travelling as repeated reflections of light through the spaces between this zig zag of mirrors, the source objects reached the viewer’s eye as images of far more stunning visual interest than their source.

Seeking something more, Brewster next tried introducing a rotating brass cylinder around the column of mirrors, so as to allow a viewer to continuously move and shift around the gathered collection of source objects to be reflected.

This breakthrough connection of light, colour and motion opened up the space for creating an “infinity of patterns”.4

Looking through the layers of glass, he saw both the transformation of reality and the creation of beauty, in ways previously unimaginable.

What Separates, Connects

Charlotte and Bob are separated by many things, including — age, generations and stages in life (he’s a “washed up” movie star unable to find a gracious path to retirement, she’s a recent Yale philosophy grad unable to find a meaning-making path to employment).

Charlotte and Bob are connected by many things, including — finding understanding in neither Japanese nor their own partners, and also, finding understanding in each other, in a way that is beyond (or despite) words.

As Charlotte and Bob wander Tokyo together, we see the invisible barrier between them and the city slowly melting away, creating space to breathe again.

What Connects, Separates

Charlotte is walking in the rain again, coloured with a longing that is silver, white and grey.

At the end, she and Bob part ways, never to return to Tokyo, because they cannot imagine it ever being the same again.

They hug a goodbye that’s both warm and silver, exchanging secrets we can never hear.

The thing about glass is that it can separate two people in an invisible way.

Overseas from Overseas

In her poem, Maggie Cheung’s Blue Cheongsam, Nina Mingya Powles writes that the dress has “the same pattern as the plastic vinyl tablecloths at roadside cafes in Singapore and Malaysia”, where she sees her mother growing up.

And it also “has the same pattern as a cloth lantern (she) bought from a shop in San Francisco’s Chinatown”, as a grown up.

Her words whirl me into a nostalgic rush of resonance.

I get it immediately, because the pink version of this fabric pattern sits, in the form of a tingkat, with me in Porto, in my now-home that’s overseas from overseas.

I’d bought the tingkat shortly after arriving in London, 13 ½ years ago, from a vintage shop in Greenwich, where I was living.

It turned out that the shop was situated very close to the Greenwich Prime Meridian, the line of the perfect middle between west and east, between my then-newest home and my always-oldest home.

Instead of food, I filled the pink floral tiffin carrier up with trust.

Trust that it would take me from London back (or close enough) to Singapore, whenever I needed it to.

When I was 26, news took its own time travelling across the Greenwich Prime Meridian to inform me that my grandma was forever lost to me, before I could make it back to say goodbye.

It turned out that, for me to be taken home, I still needed a plane to cross the Greenwich Prime Meridian, flying for 13 ½ hours in the other direction, after all.

The poem ends with Nina telling us that, at night, she can see Maggie Cheung’s blue cheongsam from the street below, hanging in her bedroom, “flooding the room with warm blue longing”.

I know the feeling of that warm longing.

Mine comes in pink, in a million little pieces.

Seeking Serendipity, Hidden in Mundanity

Sir David named his invention the kaleidoscope, from the Ancient Greek words —

καλός (kalos), meaning “beautiful, beauty”

εἶδος (eidos), meaning “that which is seen — form, shape” and

σκοπέω (skopeō), meaning “to look”

Together, it meant “to look at beautiful forms and shapes”.

Something really moved me about learning the meanings of the words behind this word, about the meaning that the inventor saw in his invention.

His declared purpose of his invention was “for exhibiting and creating beautiful Forms and Patterns of great use in all the ornamental Arts”.

Here was a scientist whose invention was sparked by serendipity, by his attention and sensitivity to the beauty he noticed, while he was mundanely repeating experiments aimed at a different purpose.

And the meaning he saw in his invention, and his hope for it, was that it would gift both the ability to better see and appreciate beauty in what already existed, and also the potential to create new forms of beauty.

Here was a scientist who was a poet, writing a poem about beauty that had no need for words.

At Least Once

When I was growing up, I never once saw my grandmother wearing cheongsams.

Mama spent most of her days at home, in functional clothing, with various hand and face towels tucked into her blouse — the better to clean the family home, cook meals and look after her grandchildren with.

“I always carried you whenever we went to the wet market. But then you turned five, and people in the market were asking me — Chan-tai, why are you still carrying your granddaughter around when she’s already so big?,” she laughs at the memory.

And she always had the same answer for them — “Because I didn’t want your feet to get tired from all that walking, you know.”

When I was a child, Mama encouraged me to be adventurous with fashion when I grew up. Specifically, she adored Elizabeth Taylor in Cleopatra. And gladiator sandals.

“When your grandma was young, she tried out almost every type of fashion. You saw Elizabeth Taylor in Cleopatra? I wore Roman sandals too, those really high ones that criss cross up to your knees,” her way was always to explain with both voice and hands (the same way I find myself doing today).

“I hope you enjoy wearing them when you grow up. Try everything at least once and enjoy it. We’re not young for long, you know.”

As we both grew — me, up and her, old — she revealed her eye for seeking out chic, comfy trainers on a budget to match her elegant clothing, since finding out she could no longer wear heels.

“Aiyoh, I can no longer fit into nice shoes,” she would show me her feet, which held in them a lifetime of walking. “Look at Mama’s feet, the bones stick out so much at the side, they’re ugly.”

I looked and thought they were beautiful. They were my grandmother’s feet.

The Flavour of Beauty

Through all these reflections of light, a thread of beauty.

I tasted this flavour of beauty as I sat listening to a haunting and unforgettable solo by the flamenco guitarist, Luis Mariano, in Granada, over two years ago.

It’s the beauty of the heart searching all around it for its own reflection.

It’s the beauty of finding the things we were always searching for, losing the things we never learnt how to lose, and in trying to bridge the gap between them, understanding all the love we’re capable of holding.

It’s the beauty of a life which shows us that we can find what we’ve lost, and that we can also lose what we’ve found, letting us see what life is actually all about.

Luis Mariano’s music floated into my life while I was wandering solo in Andalucía — newly separated from my identity, career and life in London, and disconnected from the desire to reveal this to my family, who were firmly rooted in Singapore.

(I know Mama would’ve understood at once, even without words. However, in this world, I still had words, but no longer had her.)

Looking back now at that time, I think I would still have held that secret just for myself.

But I would have wanted to tell my family that Luis Mariano’s flamenco guitar had made me cry.

Waiting for the Rain

Sometimes, when a city gets too filled up with all the secrets and longings of all the people she carries, she cries.

Have you ever seen a city cry?

I think she waits to cry when it rains, so that her tears can hide, invisible in the silver streams.

Maybe she cries, so we don’t have to.

Maybe we’ll cry, when the sun is shining, and our city has run out of tears.

Back Together Again

Wandering through life, through multitude reflections of tears and beauty, I begin to see how the stirring of our emotional reactions to things, experiences, people and places we encounter, is a signal to us of what we are, deep down, looking and listening out for, whether we realize it or not.

The alchemical bridge between the outside world and our inner world at that moment of encounter and exchange is, I think, the seed of what we ourselves want to distill from our inner worlds to express in the outside world.

The seed of what can be found, by creating from what has been lost.

Perhaps showing us the way of collecting all our missing pieces, swimming out there on their own, and putting ourselves back together again.

And that is how this story begins again.

〰️ Kindred Spirits 〰️Thank you for reading, dear kindred spirit!

I’m creating a home here for story kaleidoscopes (you’ve just read the first one!).

I’ll be seeking out collections of beautiful forms and shapes of art I admire, that move me, and that I feel want to be in conversation together.

I’ll be gathering them next to each other (sometimes with a story of my own that I feel is a kindred spirit to the others chosen) in other story kaleidoscopes like this one — letting them reflect off each other like mirrors, and opening up space for the golden threads to be woven together for each of us, as we get to know these stories, individually and together.

I’d love for you to join in the shaping and shifting of these story kaleidoscopes by sharing in the comments your own selection of beautiful forms and shapes of art (created by yourself or others) that you feel has a spirit of resonance with each story kaleidoscope.

Just as a kaleidoscope gifts us both the ability to see the beauty in what already exists today, as well as the potential to create more beauty tomorrow, from out of a heart touched by the beauty existing today.

〰️ 〰️ 〰️ 〰️ 〰️ 〰️

With special thanks to —

⟡ my wonderful friend, Rachel, who read and shared her comments on an earlier version of this piece, and whose warm heart walked me home in the writing of it

⟡ Lindsey Trout Hughes, whose gorgeous essays I love reading, for her thoughtful and cherished feedback on sections of this piece

💌

I’m very grateful to have had this piece featured in the Asian Writers Collective curation of intimate essays on grief, love, and identity by Tiffany Chu — you can read the full piece here:

Do you have your own selection of beautiful forms and shapes of art you feel drawn to add to this conversation and kaleidoscope of stories? Please share in the comments below ♡

During the Renaissance, Natural Magic was rooted in a world view that found enchantment in natural forces and physical substances from the natural world, such as stones and herbs (from Natural Magic — Wikipedia)

My friend, Helen Still , who wrote a thoughtful post about the film, inspired words I wrote that grew into the heart of this piece, when she told me — “I found the cheongsams fascinating and so beautiful, because no one else was dressed like her and she wore them as if they were everyday dresses too. Although beautiful, I can’t imagine them to be functional, perhaps it was a way of showing us how much constraint Maggie’s character was under.”

Oh Suyin, your writing is always so moving and I long to hold it in my hands so I can trace my fingers over the shapes and swells of your words. I can’t wait to have a book of yours in my palms one day.

This line really touched my soul “I looked and thought they were beautiful. They were my grandmother’s feet.” You captured that beautiful innocent gaze of a child that the world tries to snatch from us. Reading that made me feel like I was four years old again.

I also adore the section “Waiting for the rain.” The city crying and holding so many stories.

I wrote the other week about a bridge in a far off city I’ve never been to and probably never will. I don’t even know where it is. I imagined all the cars driving across it filled with stories I’ll never know.

This part of your writing captured that feeling I had even better and more poetically. I think I will always think of it now when it rains in the city. That the city is secretly crying all the pain that is held in the bodies it contains. Think of all the souls watching the water drip down windows and bounce off concrete, soaking a million pairs of feet. So stunning.

You have this incredible gift of evoking feeling within the reader, a gift I’m not entirely sure can be taught, only can exist when the author moves through the world feeling so deeply herself. Something that must be shared with the world. We need people like you that wake us up. That turn the blurring colours outside the window of a moving train into vibrant details moving in slow motion.

You are one of a kind my dear friend.

Your writing is special Suyin. It’s so sophisticated, looking at details, like something we don’t take time for anymore. It feels analog, like turning my screen into a printed book, like the air slowly cooling down after a hot afternoon on a vacation somewhere with cypress trees. I have no idea why but that’s what it makes me feel🤍🤍🤍